The Dandy & Dionysus

- Caleb Carter

- Aug 8, 2024

- 27 min read

Updated: Jan 27

OFF WITH THEIR HEADS.

Housekeeping

England is a savage rainforest, antiquity green. A surreal landscape of cacophonous fens hemmed by psilocybin groves, once pilgrims' rest and bard country, the sites of its pogroms are also its heritage. Its kings are paedophiles. Its politics are a farce. It can't escape the nightmare of class. And like a rot stuck in its rowan beard, there is an unshakable sense that something is very, very wrong and has been for a very, very long time. Invisible forces brutalise our capacity for wonder. We are told that the only way out is through but even the most gullible devotees reveal the system's defunction: to succeed means to escape, or at least to negotiate a closer retirement. Worst of all - Sorry, we are told, the system is unchangeable. Actually, we evolved to be this way. So keep calm, we are told, carry on: believe us.

Art is the Pagan snag on England's tapestry. Pulling on its threads – even briefly – has been a dizzying experience. I have come away with belief in a psychic war and hooves instead of feet. In an effort to invoke belly-magic rather than head-magic on this site (to create rather than reflect) I am usually concerned with stylistic experimentation, but I truly believe this to be a diagram whose clarity is more important than my own affectations. Unless, in places, I found monsters to be slain by spells only they would recognise, I have tried to make it as accessible as possible. This piece is about belief: it is intended to unmake one reality so as to rebuild another.

Enjoy the ransacking of the house.

Hail Pan.

"And was Jerusalem builded here

among those dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my bow of burning gold!

Bring me my arrows of desire!"

- William Blake, Jerusalem

"You gotta fight for your right to party."

- Beastie Boys, Fight for Your Right

1.

The Dandy

Emerald Fennell - Roland Barthes - Alan Clarke

Ken Russell - Camille Paglia - Mary Shelley - Percy Shelley

Odilon Redon - Roman Casas - Oscar Wilde

"It is a very British thing", my bookshop colleague said, "for the rich to gatekeep radicalism." He was talking about the late lodestar of cultural theory, Mark Fisher, but primarily of Fisher's students at Goldsmiths University, where he lectured. Three months later, I found myself at a party overlooked by Goldsmiths and surrounded by its alumni. Debating an article I had recently written on rave nostalgia, my friend told me that "it might be dangerous to think bacchanalia can change anything."

There is a long, British history of liberalism associated with its uppermost class. The radical love and populist insignias of rave culture and the hippie movements find their folklore in wild-dressing and free expression but these roots have their history in creative, sexual, and gender experimentation performed by an affluent establishment. Wilde and the Bloomsbury Group came from generational wealth, Huxley's Peyote trips were Eton educated, and the satanic, sexual surcharge of Aleister Crowley could fall back on its inheritance. Nepotism in the arts is an open secret - these days hardly worth mentioning - but sometimes a wealthy artist's popular creation, lauded for its radical dress, is in direct conversation with this tradition - such is the case with Emerald Fennell. Saltburn, suspiciously designed in the architecture of both the art-house and the thirst-trap (see neon, kink, tall boys and 4:3 aspect ratio), stirs a recognisable symbolic brew: dress, decadence, estate; drink, drugs and classic myth invoking bacchanalia; Oxford invoking Dark Academia; a gross obsession with class like a stink. Its controversial twist, in which the protagonist's working-class background is revealed to be a charade, relegates the actual working class to "the primitive proletariat, still outside the Revolution"[1]: on the benches but, probably - Fennel seems to say - underfed and underread. But it also suggests that all of the English (regardless of station) are diseased with upwards aspiration, eyes blackened with a lust for king's blood. That at the end of the Puritan revolt a chord tight and dormant was snapped in the air between the axe bit and Charles' neck, and long since has this isle been haunted by its rend.

The elite has always been into treason and sacrilege - they're expensive. Since the 17th-Century saw the translation of ancient Greek and Latin manuscripts, artists and designers have been fascinated with the geometry of ancient deities, and filigreed their clients with a marbled, muscled erudition transcending the hunched posture of the church and the state. However, like any story in which an antique moonstone is excavated and stolen from native soil, phantoms followed. For every Corinthian column erected in a bank, shadowy eroticism mimicked its trajectory, and in parlours laced with Opium, the well-dressed and well-read scored in the margins of the Iliad: “Pagans Abound”.

It will be hard to proceed without establishing this fact: the Greek pantheon is Pagan. As is the Attic, the Buddhist, the Hindu, the Norse, the Saxon. Satanism is. So is Zoroastrianism, Scientology, and Astrology. "Pagan" once meant "villager", whose rural horizon was an unscrupulous arcadia still writ in the pedagogies of storm: some things seemed to happen always (the sun rose and set, it snowed, it rained, it shone), and others (like locusts, harvest, plagues, floods and childbirth) seemed to happen at the whim of the fates. The ground never moved and the sky did but it seemed to these folk living hand-to-mouth a gross oversimplification to ascribe all of this to the big hot light arcing across it, especially when - at night - the universe uncurled. So, they built a whole cast of star-people, a pantheon, to bring more children and less fire. Like all language, the definition of "Pagan" directly correlates to the cradle of power. When Rome invaded Britain and they were charged back through the acid fog by Boudica, legions of tattooed women, white-eyed druids and moss-eaters, those ritualistic, howling people were Pagans, too. When Christianity became the richest religion in the world, anything non-Abrahamic was Pagan, and anything non-conformist was "heretic". Persecution is at the heart of Paganism, and at the heart of persecution is power.

When Oxford and Cambridge made Greek and Latin compulsory entry requirements, this was the bloody history they welcomed onto their worn stone steps. Because only the rich could access it, heretic dreams in Victorian England were bought and sold with polite seduction, degrees, a seat in the cabinet, trebuchets were armed with a twinkle in the eye and blood drawn with a bite on the lip. The upper classes - for as much as they indulged in their luxuries like dangerous thought grew on a vine - were of the enlightened type whose fetish was revolt. At night they took laudanum and laid awake staring at their window, yearning to see an orange glow, lapping, and feel its heat in their loins.

In Ken Russell's Gothic, a parable of the night that Mary Shelley's Frankenstein was created, these phantoms are made object. They haunt their creators like it is the authors who are the foreign body, the thorn in their dream-hip, and sleuth around wet moonlight like curious dogs. In a deluge of sex and opium, the writers declare "It is the age of dreams and nightmares!" But anybody who has been witness to the sublime knows that it always was, and always will be. Such stuff as dreams are made on. The sublime is "the experience of the infinite, which is terrifying and thrilling because it threatens to overpower the perceived importance of human enterprise in the universe."[2] The Gothic, with its infernal love, familial leashes and monstrous climb from the pit, reveals the capes of this strange and giant ecstasy to exist within us. Its admixture requires 1. internal infinity, 2. external awe, 3. bifurcation. A poet struck by lightning is a fantastic symbol for this experience in which all three become one and the veil of their separation (what we call reality) is momentarily destroyed. The poet becomes a forked conduit for a new world. Psychedelics are another, more accessible mediator than the spark of god. Trauma does the job too, though it is not recommended. Love works exceedingly well. Though total obliteration is impossible, the artist, during their fugue, leaves a suspended doorway ajar and night beasts free to roam. Like a muscle, like a book, something is torn - unleashed - then altered, permanently. Artists have always known that this world is clay, and that it would take the most hypnagogic of us - it would take art, and artists, once called schizophrenics, and before that epileptics, hysterics, heretics, Pagans, then visionaries, shamans[3] - to mould a new one.

It should be unsurprising that creative, Pagan forces are feminine. In Sexual Personae, Camille Paglia calls it the "belly-magic" that the masculine "head-magic" built "sky cults" to suppress. But for the guests of Villa Diodati, a wealthy circle of men who might never have otherwise come into contact with the humbler origins and radical politics of a Wollstonecraft like Mary, the feminine energy of Frankenstein was surely its most shocking aspect. Whilst her husband's most famous work, Ozymandias, is set in sand, Mary's work is bookended by an arctic desert. Sand is a cruel illusion. Seemingly refracting the stardust we are all the updraught of, its project is ultimately that of more sand. Conversely, the tundra feels like it is the bane of us - a wasteland of knives - yet locked in its ice is a more cyclical mode of oblivion, life's current in soft stasis. The middle of Frankenstein is the glacial pool into which its appendages thaw, the bifurcation that allows awe to flow into the sublime: Frankenstein's monster speaks. The structure of Shelley's book is that of an amniotic manger that recognises life as a continual wheel of birth and death and, in the name of this continuum's divinity, is furious at the burden of its master's "progress".

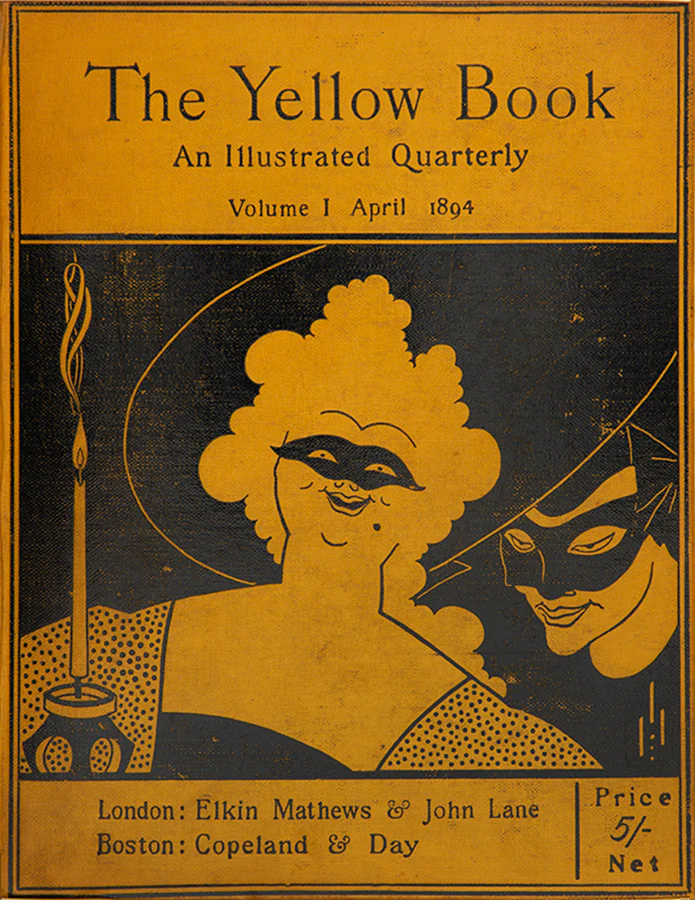

It's 4 am. The dance is over. The century is about to turn and the world with it. We got drunk in our funeral attire and then lazed on the cushions of England's verdant hills to preempt the death of the queen. "I reckon she's only got about three years left in her." Leafed through our hands: the manuscript for all our prophecies, The Yellow Book.

“His eye fell on the yellow book Lord Henry had sent him […] It was the strangest book he had ever read. It seemed to him that in exquisite raiment, and to the delicate sounds of flutes, the sins of the world were passing in dumb show before him."

- Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

That golden portal, whose colours were the insignia of wealth, Mithras crowns, idols, claws, and The Golden Dawn was the serial manual of spies for revelation. Its writers were a chaotic class of enfant terribles who knew that ploughing a new century could only ever be done over the bones of the old.

2.

Dionysus

Aubrey Beardsley - Arthur Machen - Donna Tartt

Peter Paul Rubens - Caravaggio - Nils Blommér

Friedrich Nietzsche - William Blake

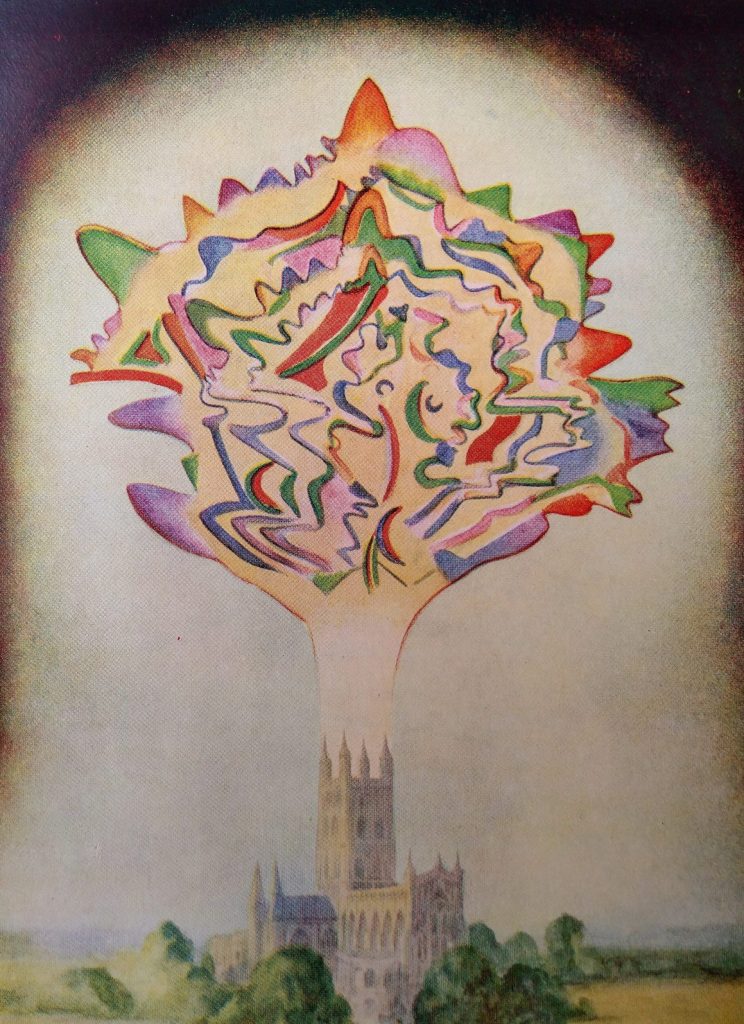

Illustrated with Aubrey Beardsley's bawdily violent inkblot wraiths, The Yellow Book's contributors included, amongst others, W. B. Yeats, H. G. Wells, Henry James, Oscar Wilde and Arthur Machen. Machen was a clergyman from Gwent but he gave it up to become a Pagan. In his novelette, The Great God Pan, London is besieged by an emerald mania. Pan, the Greek satyr who instils pan-ic in those wandering astray, is in Machen's fragmented depiction transgender, and a shapeshifter, virgin girl and virile beast, nubile and pubic, silent, bucolic, reeling, ravenous, "the form of all things but devoid of all form [crying] 'let us go hence to the darkness of everlasting.'"

"That woman, if I can call her a woman, corrupted my soul", Herbert cries to his old university chum, Villiers. Once privately educated and coasting on his family's investments, Herbert has accidentally married the ancient daimon, Pan, in the shape of a beguiling woman. Now she has "corrupted" him, and he has willingly sacrificed his inheritance to her as a result. The intonation is clear. Herbert has been sodomised, and the experience has not only ransacked his marital status, but dwarfed the importance of his material world. He is ruined - he believes - by the true nature of evil. And yet, Dr. Raymond, bent on unleashing the beast and forcing its coarse, green goat hair up through city cobbles, considers the implacable phantom a prehistoric continent - the axiom of our origins - the "real world" behind the "dreams and shadows" of our waking life. The true evil of nature: chaos infinitely rebirthing itself. Fitting to Herbert's experience, whose previously unknown centre has been reached, this ruin is entwined with rapture.

"It was heart-shaking. Glorious. Torches, dizziness, singing […] The river ran white […] Duality ceases to exist; there is no ego, no 'I' […] as if the universe expands to fill the boundaries of the self. You have no idea how pallid the workday boundaries of ordinary existence seem, after such an ecstasy. It was like being a baby[…]"

"But these are fundamentally sex rituals, aren’t they?"

- Donna Tartt, The Secret History

Pan was a foremost member of the Thiasus, an ecstatic parade of satyrs, sileni, nymphs, and the frenzied human maenads (whose name means "to rave"), led by Dionysus, the Greek god of fertility and wine. His migration was, by varying degrees, a war charge, funeral march and birth fete. On reliefs found in the Vatican, the Louvre, and the British Museum, he might be depicted as an old, wise, drunkard or as a beautiful, young man, and Pan as either a foul faun or a crowned ephebe tugging at his thigh. Like his esquire, he is a shapeshifter. In Rome, he was known as Bacchus, elsewhere as Zagreus, son of the underworld. He is the darkened hemisphere moments before tillage, a two-sided coin whose dual kingdom occupies magic both of its sunder and its meld.

Actual Dionysia, like the mysterious worship ritual enacted in Donna Tartt's The Secret History, was immersed in fluctuating gender identity. Its rites were spread throughout the year. Oscophoria gave us costumes and food in October. During it, twenty young men and boys raced boughs of grapes from the temple to the harbour, and the fastest boy was rewarded with a goblet of (possibly psychoactive) honey wine. Once drunk, he wore a woman's dress and led a choir to a banquet and animal sacrifice. Expectation fell away. The freer you acted, the more fertility magic you freed. However, these festivals were exclusive, frequently to men and inheritors of vineyards and breweries, and state-sanctioned.

Unlike in Thrace, where they say they can hear orgies in the clouds, ricocheting against crag and crevice, savage moans riding down on the mist, and on Parnassus, they say to stay indoors when the women and girls perform their own fertility rites to usher in Spring. They dance through woods up to the mountains, crowned in ivy and snakes, screaming with wands brandished, drumming palms red-raw on hide. They slit the throat of a goat and then tear it apart with their bare hands and eat it, just as the Titans did to Zagreus. That is not wine on their lips. They don't play trick-or-treat on the doors of the gods, they consume the flesh of the satyr, its gore still steaming on their chins. These rites invoked Spring with the chthonic force of feminine libido, cyclically sprouting from the underworld on the reflux of lava, rather than a momentary bestowal of pyramidal - masculine - Olympian grace. Not crown shy, it is the faeries' connective praxis that harks a crushing daybend.

Dionysia, stuffed with secrets and drunk on their revelation, permitted its initiates to indulge in powerful luxuries and revel in the hallucinatory expanse of a boundaryless shore, the sublime. Friedrich Nietzsche's The Birth of Tragedy is primarily concerned with describing the artistic conflict between the Apollonian (illumination, form, prudence, purity, reason) and the Dionysian (instinct, impulse, music, passion, chaos), more abstractly for the seen to coil around the unseen, two faces Nietzsche respectively terms "dreams" and "drunkenness". Dionysus is a powerful god but, like drunkenness, an erratic one, twilit, a close heat streaked with seemingly random aurora borealis. Alexander owed much of his violent crusade to Dionysus. He is the lush power of the evening, the lantern, the grape, the orifice, all that is crimson spilled onto mud. To indulge in all at once is a violent kind of ecstasy. So closely wed, it's what Nietzsche described as "that horrible mixture of sensuality and cruelty which has always seemed to [him] to be the genuine 'witches brew'".

In 183BC the Roman senate outlawed then violently prosecuted Bacchanalia. Not for its pantheon (though that would soon follow) but for its excess. Dionysia was the terrifying symbol of the people's bottomless demands - an insatiable, ungovernable want - and marked the beginning of a long history of social rituals being prohibited by the state and then privatised behind a mask.

3.

The Ritual

James Ensor - Stanley Kubrick - Frederic Jameson

Slavoj Žižek - Balthazar Nebot

Patricia Highsmith - Anthony Mingella

The invitation is red with gold inscription that can only be discerned by candlelight. Above the flame it reads: ET DIABOLUS INCARNUS EST. ET HOMO FACUS EST. You choose the mask of a dog, presuming it would be fatal to wear the face of an ungulate. You are no lamb. No sacrifice. Upon arrival you are offered tea. When you drink it, reality unrobes. Wading through the shimmer, you make your way to the highest floor of the highest tower. God's assassins stand in dresses wearing the eyes and horns of goats. They undress. There are drums. They get on all fours.

Masks are theatrical and gnostic, of a material-spiritual accord, insinuating esoteric tuning to hidden truths. Of course, that truth may be nothing more than the ashamed identity of inherited wealth (this country is sick on class at both poles - the difference being that whilst one blushes, the other starves). But anonymity also more easily permits foreign entities - the radical, the poor, the migrant - to enter its previously consecrated arcane circle beneath the cover of ceremony.

In Stanley Kubrick's final, most mysterious film, Eyes Wide Shut, masks hide but they also contain and curtail. The elite license the id in secret, wassailing by moonlight in an exclusive libido ritual that keeps the world-movers' demons at bay. Like the state-sanctioned bacchanalia of Rome, one-orgy-per-bank-holiday keeps away that uncontrollable bastard, desire. Subsequently, polyamory and homosexuality become delicacies for those that can afford it whilst the peasants' war with the concept and politics of heteronormative marriage, still mashing spheres into square holes. Meanwhile, the orgy's exclusive, Pagan coding, masques, cloaks, the baroque (notice ingredients for cabalist conspiracies; the Illuminati, the red shoe group, Black Rock's undisclosed investors, Freemasonry), terrifies in its suggestion of capitalist worship. With an undecipherable costume and ritual mode, it is not just a monotheism, but a many-tendrilled beast requiring devotion to a perverse pantheon, stirred, freakish, and immovable in its number amongst the pinprick hernias of the stars. Jameson and Žižek say that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism[4], but the same now goes for its beginning. The Party both predates and outlives its guests. Despite ostensibly being its arbiters, they believe in the system as one believes the skies will bring fields of gold. It is the prime mover.

Like class, Saltburn from the beginning is about sex as a mask. Oliver weaponizes his own sexual fluidity to infiltrate the higher classes of the estate: the more rich people he sleeps with, the longer he is allowed to stay but, pointedly, he is refused Felix's body. Whilst he degrades himself in sexual sacrifice, drinks used bathwater, and kisses rainbows, intercourse with Felix is considered a higher transgression than murder. It is easy to assess why anyone would want to have sex with the rich, but taboo to wonder why the rich would want that too: to entertain their fetishisation of the working class, maybe, but perhaps also because of a primal, erotic urge towards metamorphosis. If sex is, as Camille Paglia writes, "dream's proving ground", then penetrating the rich man is to enact a power reversal that transcends wealth. Impulse is the devil to tyranny. Once brought to orgasm its despotism goes soft.

The tacit understanding of Dionysian ritual - whether art or festivity - is that rebirth comes at the behest of oblivion. This process is what we might call revolution. The seduction of reversal's threat is that of sexual domination, and is laced through the homoeroticism played out in all of the art inspiring Saltburn. From Dorian Gray through to Patricia Highsmith's The Talented Mr. Ripley, its archetypes dance the boyish hunger for male acknowledgement, answering that ancient adage, "I'm not sure if I want to be him or be on top of him", with "they are both the same thing." In Anthony Mingella's adaptation of Highsmith's novel, the moment hyphenating pretence and violence is most important here, the "Oh, God" and "Please no", the thin line between a moan and a groan and the seconds in which every lie - personal and societal - collapse. The consequences of refusing to participate in the game or simply naming it as such come to light, and the iron tang of truth emerges: the rules are predicated on violence.

Unwilling to break completely their bondage and draw blood, the uninvited guest (jagged novitiate, Zero, the fool) is not an anarchist to but a participant in the schema of The House. They want the crown of thorns on their master's head for themselves, the sceptre and robe, its signs and symbols and, ultimately, to fuck The House on its way down. Partly as gleeful revenge, partly because The House wants it, too. The equilibrium of capitalism is sadomasochistic. The bottom's submission is pre-requisite to the top's continual gain. The highest percentile is a leach, a vampiric power relying on its host for sexual mana. Its infertility unmasks both its weakness and its identity.

4.

The Witch

Alan Moore - Annie Besant - Silvia Federici

In The Great God Pan, men who are "rich, prosperous, and to all appearance in love with the world" are driven to suicide by a magical force. Less than ten years before its publication, women of London forced into prostitution were brutally murdered by a man. The hysteria besieging the aristocracy of Arthur Machen's story is the direct and imaginary inverse to the Jack-the-Ripper murders. Suddenly, the subconscious, feminine power at the heart of Machen's tale takes on a vengeful quality.

In his deep, anarchist conspiracy, From Hell, Alan Moore uncoils from those murders an umbilical map of England on an ocean of blood. Chapter Four tours a satanic Albion beneath London, firmly locking a patriarchal evil in its street-names and corners. Moore traces Freemasonry to the dark elf Dionysus himself, a worship of phallic, sacrilegious sun-and-stone cemented across epochs of architects beginning with the craftsmen of Atlantis. Its acolytes choose chaos as the paternity of progress, worshipping his signs littered through vain crucibles: the hadron collider, medicine, war... Let's take stock: something here has shifted, hasn't it? Once the scourge of the powerful and threat to order's collapse, The Dionysian now seems the magic idol of tyrants.

Signs are precious. When we imagine the authors of society as a cult, wearing the peach-rot gore of a goat, we reinforce wealth as a gravitational force, its gain incandescently broiled like alchemical gold, and when we enchant them with Paganism we also apathetically sacrifice our own symbols of heretic rebuke. We lose our inner power to manipulate the very signs that write reality.

A lesson in witchcraft. The human mind is pliant and the human body is fragile. Signs are crucial to the survival of both. Usually spells need a material: dyes, ochre and charcoal, brews, herbs, entrails, whole bodies, foals, goats, new-borns. Or a spell might need the body itself, milk or blood or hand movements, dances, romps, fucking. But most important are signs, words, symbols. The soul is on the breath. The ground can rift if you name it right. It's a survival mechanism as old as humankind: if you feel yourself losing a tether on something, or you're cold in the wet cave and facing down the hot snout of some deep dark beast hitherto unknown, naming it might buy you some time. Signs, placed in correspondence, create order from chaos. Chaos - its pulsing, protean, ever-unfolding nebula - is what in Hebrew is called the Ein Sof, the "(there is) no end", over which a fortress of nodes called Sefirot's are placed to form the Kabballah. We might think of any system formed likewise, from class to capitalism to relationships. The more complex the web, the greater the strength of its chains.

I choose to find glory in the unexplained, as even when explained I find more glory still in consciousness. There is little to suggest that anything I have written above predates us and our imagination, but that only makes it more glorious to me. All the cosmos from our skulls. Trying on various garments of belief is, if we are to listen to the anecdotes, one of the most exhilarating experiences life can offer; perhaps the reason we are here. Nevertheless, it is worth decoding for a moment the systems of the elite as simple nodes of a map. A powerful one, but one whose total diagram is a misdirection, casting the illusion of an arch-lord presiding over what is in actuality a very real, tangible, walking, breathing, bleeding power. Their power is a global and spiritual defilement – founded upon crusades and enslavement, homogenising international "progression", selling productivity at the cost of individual wants, pains, identity and communal property, then palming blame on to anyone uncategorisable (categories are the ammunition of hate). But you don't need to work as hard as their logic suggests. Get off the bus at the first stop. The people you think are to blame probably are to blame. Their motive probably is money. You can see their faces, say their names. Our minds are wired to acquiesce patterns which are of great comfort to us: like prejudice alleviates pain, ghost stories, conspiracies and mass hysteria are ways to band together and consciously illuminate the terror in the dark, but this can be weaponised to confuse and divide us. There is an even more terrifying story than Jack-the-Ripper. That there was no plan, no plot, no pattern: that a group of men with bile in their hearts, in isolation of one another, perhaps without ever even meeting, used his haunting as a mask to murder women.

Patterning hysteria is a classic patriarchal tactic to keep the lower classes divided and thus suppressed. In colonised states, they also give them a nationalist party to channel their anger through. But any form of suppression is a sign of what the suppressor fears. If sex and homosexuality are actively suppressed by a church or a government then it is only because they recognise it as a challenge to their reign of confining domesticity and caste. They rearrange the nodes on the map and turn sex into a symbol of shame, and its vast, unmitigated drunken ocean is compartmentalised into fetish, perversions and sin, meanwhile still profiting off other channels of desire. If women can derive pleasure from themselves and each other, then reproduction of a workforce suffers, and "promotion of life-forces turns out to be nothing more than the […] reproduction of labor-power."[4] Gender as it pertains to capitalist gain is revealed as an illusion, and the participant is free to wonder what else is a lie. This is the power of Eros, and the Dionysiac state where categories fade. The moguls and technocrats behind the mask of Kubrick's orgy fear this sex magic. They want it exorcised from their kingdom. The witch trials of the Inquisition were not a war against magic, but a systematic gender apartheid on the supply of labour, seizing the means of re-production through patterns of fear. Via this historic and ongoing femicide, the inviolable matrescent coil is clipped, neutering the very human (and very accurate) intuiting of the infinite. Dispossessed of its grace, but possessed by the (very accurate) fear of its spiritual survival, the patriarchy sought to lock it into the ruling religious symbols most close-to-hand. An incestual martyr who is sacrificed by his father to be reborn as the seed, the child and the womb in one. One only has to overlay the cypher of the holy trinity onto these facets of reproduction to deduce who has been murdered yet feared unkillable.

5.

The Migrant

Brian Welsh - Mark Fisher

Pier Paolo Pasolini - Vinca Petersen

Dionysus is a god of cycles. His power stems from fluidity and mobility. Taken prematurely from the womb of his mother, Zeus stitched the unborn babe in his groin until he was ripe. He is both woman and man. Once born he was an itinerant child, taken to the nymphs of Mount Nysa to be raised on the babble of nature. His position at the head of their procession is because these forces care for him. He was raised by their demon hamlet and it was born to move, a whole caravan of travellers mimicking the circadian rhythms of a universal continuum. Wake with the sunrise, walk so as to walk, commune, regale the day, sleep with the sunset. What else ought there be?

Drugs and music are the great cultural equalisers. Psychically flattening boundaries, in a room full of electrical conduits a synaptic truce is struck. Hallucinogens are a mask, exiling isolation and draping the veil of ignorance over its subjects like a no-face upon which the crows feet of the gods can perch. The closing rave of Brian Welsh's Beats is stormed by riot police, and yet even as they brutalise the dancers it is hard to tell if their presence isn't just another ecstatic zap in the rush. The conflict, bruising confinement and blind duty of British law feels present even without their batons, in the sweatiest of raves where something is exorcised and the hands thrust into the air are fists. When you dance at a rave and are joyfully communing beyond the demands of austerity, it feels like knocking on the beats there is an opposition. In the bullets shelling against concrete in the music of Burial, the hardcore northern subversion of Makina, and the warrior bardship of MC's like Mike Skinner who is "45th generation Roman", the music sounds, in some distant sense, like war. Against the anonymous ideology[5] of our current state, we are lorded over by a mythology that is disembodied: sit, paralysed, ctrl-c, ctrl-v, spend to sit comfier. It might take returning to the body to destroy it. Paganism is so often seen as a resurrection of muddy, nonsensical, primitive traditions predating the spiritualism of church, but at its root is a radical cosmic wonder. In bodily action, categories lose their potency: to dance is to dance, undictated, and anything that transcends the polis has the power to dissect it.

Like the Roman senate outlawed bacchanalia, it's no wonder that free parties in the UK are criminalised, being the invisible, psychic meetings of the creative and the liberal. Across the history of Britain, subcultures have been perennially demonised by the government. In Mark Fisher's crucial essay, Baroque Sunbursts, he deems the "cultural exorcism" of 1994's Criminal Justice and Public Order Act that effectively outlawed publicly organised raves to also be one targeting the "unsettling and unsettled figure of the fair." The fair, a roving beast of storytelling that combines decadence with market was the unpinned butterfly to enclosure. Capitalists see its form not only in free parties but in football terraces and travelling communities (all of which were havens for the working class). Criminalising one, buying out another and festering hate for a third allows governing bodies to privatise, survey and police modern Dionysia. Hypocritically, whilst a landlord can cry to court after suffering a restless night over the shrill sea-call of brat druids, an initiation of ritual sex with a pig's head at Oxford University is permitted beneath the regulations of wealth, tradition and boyhood.

"Through the love you gave me, I've become aware of my illness."

- Pier Paolo Pasolini, Teorema

If an extra-terrestrial visitor drew data from the way humans narrativise their lives, they would quickly conclude that the greatest gift they could offer someone who believes that they are complete is to remind them of their absences. The capitalist amphitheatre is an existential bubble, and social mobility a pin. In Teorema, a rich family is ruined by an unwanted guest, but unlike Saltburn there's no real need for bacchanalia. The family desire the visitor but he doesn't need to seduce them. Like the working class to Fennell, he is an unimaginable class of people, stamped out by a faceless order, then resurrected like a fairy-tale who is lusted after simply because he does exist. The world hypothesised by the bourgeois is a desert and so, aware of this fact, when a note is delivered to their sepia fortress that proclaims the visitor is "arriving tomorrow", they think "Thank god! It was not all for nought! And even if it will be the end of us, we will finally have earned something beyond our control. Now we can laugh and make nonsense and drink nettle beer and our children will heal via illness which will leave space for miracles again."

The itinerant, the experimental and the uncategorisable are dangerous to the stagnant and the ordered. At the root of bog-standard, British hatred is this delusion, too: that they might lose all they have known because they have never dared to imagine better. They will tell you to justify your existence through work, but simply by moving through The House and existing at the intersections of gender, of class, and of sexuality, you weaken the forces that seek to oppress you. Your power is immanent.

Dionysian magic is anarchic. Rather than the targeted, channelled divination of the other Olympians, Dionysus can choose to unleash his retinue upon his enemies, but beyond the opening of the floodgates, he has no control. The Bastille is stormed. In the many accounts of his excessive judgement, there is always the sense that it is his troupe who are the true, free agents of chaos. To their god, mutiny would be disaster.

6.

Pandemonium

Alison Rumfitt - Lars Von Trier - Peter Shaffer

Defeat is often swept beneath cause; big fish eaten by bigger fish. This is the same process as the Apollonian senate wearing the head of Pan. Moore suggests the new hope of the decadent 19th century were defeated by the crown, suffrage subsumed by empire; Fisher that rave was eaten by radio, glitch by surveillance. Those left wandering the striated wastes of centennial dawns are so often babes amongst rubble, just the dirt and ephemera of the sabbath. This is where we find ourselves, one quarter into the 21st, warbling a caged wail through hyperpop and memes. But in an eternal war staged in cycles, defeat is rarely defeat, and the goal now is to be loud, press the thumb on the screw in evil until the stars further dislocate and the planets are to play for, with foot on neck, with knife in side, with whisper in ear, in number, in body, in mind, in spirit. They've left the door unlocked. We are already raving through their house.

Pan is a daemon, not an Olympian. A god belonging to the Turning Land, his biography is not as laurelled as Dionysus. He is the Arcadian god of pastures, protector of flocks, herdsman and hunters, yet he freely passes into his tribe by way of his terrible arts, song and revelry, wandering up and down the retinue as he wishes. Similar to Dionysus, he was also born from Zeus and a nymph. His origins are the same and in the braided vortex of shape-shifting and legend, the two are frequently mistaken. By the time they got to Rome, they had merged entirely. If Pan the peasant is not the same man as Dionysus the god, then he could very easily take his place.

In Equus, Alan Strang, whose hoof-foot Pagan chorus are the only non-imaginary object on stage, is sick as the earth is sick. His condition is feeling the divine within nature, his depression is that it has been choked. His defence mechanism against the probing Dr. Drysart is to sing jingles from adverts on the television his father warned him would rot his brain. Strange for a boy whose god is a horse, rather than recite the Westerns his mother covertly let him watch, his sensitivity to advertisement in particular reveals the co-opting of poetry, light and symbology by consumerism. These brands, when transplanted onto a choir of old gods, disappear into a disturbing pantheon:

Gog Google Gomorrah Sodom Trident Tesla Tut

These are names of new titans wearing the masks of heroes whose tenebrous mythologies daily molest our minds. There is no free land left in England. Conservation is owned by royalty. Those destroying land for profit have an environmental department. Just as Hadrian built a wall to confine and exclude, England sinks deeper into its fear of what lies on the other side of what it has taught.

From Nietzsche's rallying cry to Paglia's redress, both outdated, treatises on the Dionysian are laced with omen. Early in the former, Nietzsche calls for transfiguration to be dosed intermittently, initiating a duality in which the inner spectator is – if pacified – still onboard. Alison Rumfitt’s generously transgressive firebrand, Tell Me I’m Worthless, leads the reader into the bloody chamber of England to surmise its relationship to nature: "inside the room is the pain you know, outside the room is the pain you do not know." And in Antichrist, Von Trier brutally hypothesises woman-as-evil, as arch root rot, screaming "CHAOS REIGNS." We are dealing here with the ascription of evil and the subsequent drinking from its pool. Well, I propose that we have been too cautious. The scales are greatly uneven.

It is worth staying within the room only to investigate its obverse scar morass, its "NO TRESPASS" signage, swastika tattoos and racist graffiti, and to trace the handwriting so as to recognise that even though in the dark, dark woods, no child can be promised safety, the cottage is no protector either. Its system's only power is fear, which is itself a belief in the system. Nature's unalienable continent is within. Anger must be directed in accordance with the correct signs. First, unlearn. Disenchant their circle to reclaim the components you need, destroy those that you don't, create what's missing and rebuild anew. Woman is nature is the devil is the black pit that appends us, upends us, ends us, and waits, but only insofar as it is the agon to England's patriarchal rubric. Naming abuse is power. Recognising also the abuser's garb of Natural Order as camouflage - and a sin - sees that if his crown of roses weren’t rotten he would bleed. Once learnt, then harnessed, the signs within the room and without can be rearranged to Frankenstein a nation like Shelley's own Caliban of light, who is native and reverent to the perpetual pale which gives them wonder, but was impinged upon by a crude thirst and is now entering an age of vengeance.

Belief is insinuated to be the programme of children. Children, beyond the veil of ignorance, must believe. Adults, gaining knowledge, lose the capacity to. I have mined through the symbols of England and told – like all English myths – an immigrant song of snoring, mongrel gods - half moss, half sea - and the fires of greed, attempting to define a clearer line behind the complex chords and draw out this Manichaean world of light and dark, good vs. evil. This land from tip to foot is an illuminated manuscript of hexed glyphs. Everything is a symbol when transposed within, and when believed in anything can be writ anew.

Belief is what I am calling for, in its most evil, splendid childlike form. As close to the dirt as possible, rolling in daisies with butterflies and lambs. As a child, unfettered by the scorn of invented doctrine and indicators, truths present themselves in visions as lucid as the Spring, most slow and honourable. Like: art should be free. Wealth disparity is cruel. Our politicians knowingly kill. And when someone uses masks to try and place distance between you and these visions, simply see their own inner child and respond to them as such: shh.

No one is born bad, but most artists know that evil exists within all of us. When the right signs are arranged in the right order, it alights. There is an ancient war being waged on multiple fronts - not least of which is inside you right now - but one ritual at a time it can be unwound. For those of you reading this who, in your great hurried shame to mask your fear at being a living thing and wasting your finite time, are still loudly appealing for a state of lies, for hatred because it is the closest thing at hand, and against the true liquid world that exists within us, between us, and beneath this mossy scuff: we have heard you loud and clear. Don't expect an invite to the party. At the very least, you'll have to get on your knees for one.

"Brace yourself, 'cause this goes deep

I'll show you the secrets, the sky and the birds

Actions speak louder than words

Stand by me, my apprentice

Be brave, clench fists."

- Mike Skinner, Turn the Page

[1] Roland Barthes, Mythologies

[4] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?

[5] Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body & Primitive Accumulation

[6] George Monbiot; Peter Hutchinson, The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism (& How It Came to Control Your Life)

Comments